A few weeks ago I was walking a friend from a small city around Chicago’s Loop. As we walked, I pointed out details about this and that building, how things had changed in the 40 years since I first started coming downtown regularly, and she marveled at the city – at least I like to imagine she did – and its brawniness.

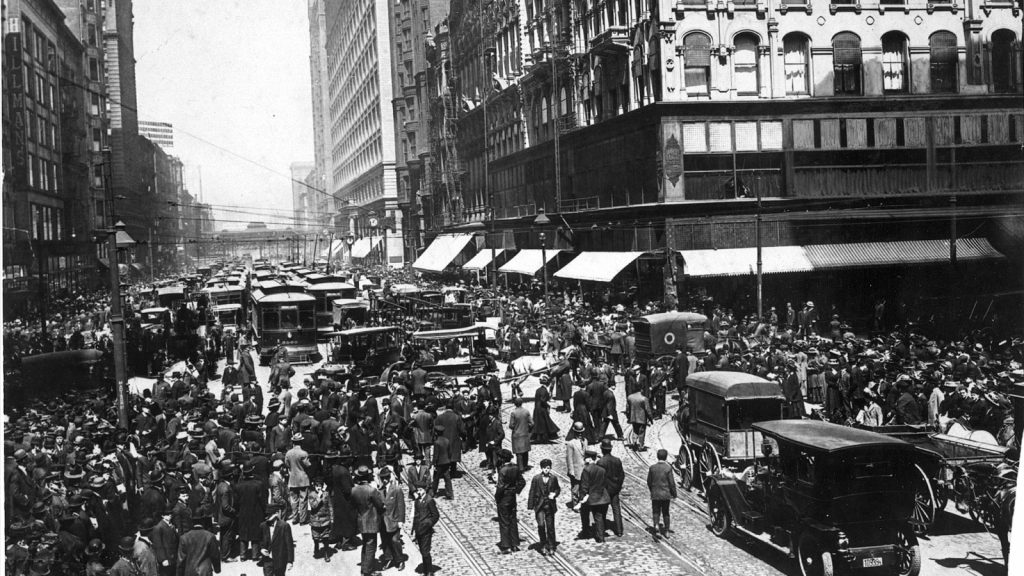

I felt proud of my city then, as I have so many other times I’ve shown out-of-towners around. My hometown’s downtown is brawny. It is made for commerce and teeming masses of people, rushing from one place to another.

At the tender age of 11, my mother would drop me off at the corner of Randolph and Michigan, where I would skitter down the stairs to the underground South Shore Line station, on my way to the orange train to Indiana for visits to my grandmother’s house.

Permanently fixed in my brain is the cold, damp smell of the underground tunnels to the station – renamed “Millenium Station” when it got a makeover twenty years ago – and the sound of shoe leather scratching across concrete in a rush to catch trains. If I didn’t keep up – even to linger at the nearby newsstand to gaze at the candy for sale – some towering, rushing adult would bowl me over as they rushed toward their train to Beverly Shores.

Rather than be intimidated, I was energized by the purpose and energy of the scene. Downtown is where I wanted to be! That is where people were doing things, and the lore and excitement of Chicago’s big, bustling core filled me with ambition to be the same.

Those were the thoughts that filled my mind as I rode downtown last night on the L, for what I once calculated as at least 7,000 trips. WIth plans to meet family for dinner on South Michigan Avenue, I realized I had an hour before dinner, so I detrained a few stops early to walk around the Loop on a clear Saturday night.

Almost as soon as I stepped off the platform onto city streets I realized the distance of my memories. The streets weren’t barren, but they were far from full. Winding through downtown, the reality of emptiness struck me harder than ever before. A once busy 7-Eleven, now gone. The Walgreens that now closes in late afternoons rather than evenings. The McDonald’s that’s gone.

None of this was new to me – I knew these places had faded away during the pandemic. But somehow the totality struck me harder yesterday than it had in a long time.

Tourists and college students still filled the bigger streets – Chicago’s South Loop has one of the biggest student populations in the country – but side streets felt thin and bare in a way I’d never experienced.

This was not the full, bustling downtown I’d come to love. It was something lesser.

It was at that moment that something sickly clicked in my brain: Mine is not a brawny downtown anymore. It is the emaciated frame of a bodybuilder who long ago stopped lifting, stopped eating, withered into sticks.

Data from Kastle Systems, the security company that operates the ubiquitous key card systems, shows that on Chicago’s best days, Wednesdays, the downtown is still only 45% as full as it was before the pandemic. On Fridays it gets as low as 30%.

To put that in numbers, in March 2018, Crain’s Chicago Business reported there were over 670,000 jobs in downtown Chicago. That means that now, about 335,000 fewer people are downtown on the city’s best days. That’s like all of Sioux Falls, South Dakota not showing up one day.

Looking around my drastically emptier city I feel like the downtown is no longer built for this moment. For 150 years, Chicago’s downtown coursed with people and commerce. You came here to do, never to linger. It wasn’t built at a human scale, because it was filled with so many humans – all the time.

But reflecting on my time in Europe this summer, thinking about the downtowns of Paris and Stuttgardt, I can’t help but think about those built environments with more niches, walkable places, benches, trees, and welcoming, smaller storefronts that beckoned you inside, to linger and browse.

Instead of commerce, European downtowns were built for living, filled with creature comforts that entice you to stay a while. In contrast, Chicago was built to get you there as fast as possible.

What happens when you don’t want to get anything in downtown Chicago?

I don’t have any answers here, but the worry I have is that without some major changes, Chicago’s downtown – and many others, will never be able to lure the crowds back.