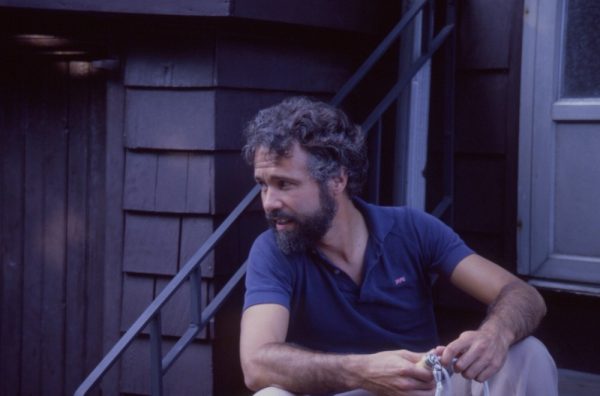

Lou Fourcher was far from perfect, no man could ever be. But as his only child, I was showered with love, encouragement and wisdom like no other. Of course, he and I had our fights, but they were usually because of my own impatience, rather than something he did.

“He was a man completely without guile or ego,” remembers his long-time friend Steve Wheatley, words that described him perfectly as a father.

My mom and dad divorced when I was two. It was a sorrowful split, but friendly. Dad moved a short distance away, within walking distance in Chicago’s Hyde Park neighborhood. He gave me as much of himself as he could, with two overnights a week in his series of tiny studio and one bedroom apartments. I didn’t notice their shortcomings, because we played and played together with Legos, trips to the park and my favorite, a make-believe game called “Emergency” where I’d climb in his lap, and he’d make helicopter noises as I pretended to pilot him to find a person in need of rescue.

Those years when he was single and mostly poor, bound us together as tight as you can imagine. A cerebral man who just couldn’t figure out how to make money, the 1970’s were slim for him. A big weekend outing for us would be to go to a Sunday morning matinee, which were extra cheap, and maybe to the Museum of Science and Industry for the one hundredth time, which was still free back then.

One extra slim Christmas when I was six, Dad told me he could barely afford presents, and definitely not a tree. So, in a stroke of genius, he suggested we cut out our own ornaments from magazine ads, and hang them from his rubber plant with paper clips. Topped off with a short strand of blinking multi-colored lights, I was tremendously proud of the tree my dad and I had made together. Years later, in wealthier times, we’d recall the “ornaments” with gales of laughter. We had us, and I loved it.

Later, when I was eight, dad remarried, choosing a wonderful woman, Penny. She was warm and caring, with two older children of her own from a previous marriage. Dad and Penny also eventually split, sorrowfully but amicably, but for years Dad and Penny loved all us step-children, and their home became a refuge during my bumpy teenage career.

Through the years, Dad, a natural athlete and one-time captain of his high school football team, gently encouraged me to get outside and play sports. A bookish kid, I resisted fiercely, but he persisted. In my pre-teens, he pulled me outside for long walks to the park with a baseball and gloves he kept to play catch. Then, one Sunday afternoon we stumbled on a pickup softball game. He pushed me to join, first volunteering himself to play. I had never played any organized sports, but that game, and the following Sunday pick-up games in that field with my dad and neighborhood kids, converted me into a baseball lover.

Middle school and high school were difficult for me. Enrolled in an elite private school, and constantly told I was a smart kid, I still struggled in class and often erupted in fits of rage. The elite school setting didn’t fit me well, as I was acutely aware of the income disparity between me and much wealthier classmates.

My father, and his home with Penny, was where I retreated every weekend, to prepare for the week to come. More than anything, he gave me empathy, as I’d yell, rage, cry or just sulk through my twice-a-week visits to his house. It was a relief from the pressure cooker I believed teenage-hood to be. When the weather was warm, we’d walk around Hyde Park, bouncing a ball between us on the sidewalk. I’d talk about whatever, or not, and he’d just be there.

We usually ended up in the many bookstores of Hyde Park, and I’d struggle to stay entertained, as dad plunged into the philosophy, sociology or anthropology sections stocked for brainy University of Chicago students and graduates like him.

“Ooh, I got some good ones,” he’d say, and I’d glance at the long, meaningless titles, wondering how he stayed awake when reading them.

His bookcase was magnificent. Self-built, it was far from artful. It was just really, really big. Hundreds of books, all of which plumbed the mind, the psychology of inter-personal relations, or just something super deep and full of academic gobbledygook. He read them all, filled them with underlines and notes in the margins.

The bookcase was in the same room I slept in at his house, so as I drifted asleep, I’d admire it wondering if I could ever be so well read.

Noticing my interest, Dad gave me books of my own. They were often hard, always challenging. Biographies of people he thought I should know and admire. Edward R. Murrow, Saul Alinsky, George Orwell, Phil Burton, Robert Moses. The lives in those books set my mind on fire. They enabled me to dream big, and set my own course for working in Congress, starting my own news publication and believing that I could change the world for the better, just like my dad.

If you knew him, you understood that Dad believed that fighting for social justice was the highest calling a person could answer. The first in his family to go to college, he found himself pulled to the civil rights movement almost immediately after leaving his small New England town. Once, as part of a group of white students who attended the historically black Morehouse College in Atlanta for a semester in 1962, and then joining Martin Luther King, Jr.’s March on Washington the next year.

As a graduate student, he was part of one of the first community health centers, the University of Illinois-Chicago’s Valley Project, in 1971. That brief stint led to a stunning set of photographs he took of people living in one of Chicago’s poorest ghettos, and then a life-long passion for community health care.

Although he was a practicing psychologist, Dad’s real career became managing community health centers across Chicago, most in neighborhoods devoid of investment and ignored by white society. He pulled me along to his jobs, pressing me to volunteer, where I inflicted patients with my high school Spanish, and learned about a world my elite private school barely acknowledged.

He was selfless in his commitment to work. There were plenty of people that needed much more than he could give, and they were ignored by society, he’d say. If he could make a difference, he would try to do his best.

His passion for fixing society’s ills never included personal glorification or accolades. He was embarrassed to be recognized for his work, and when we was, by me or others, it was uniformly met with, “Well, thank you. That’s enough, now.”

It’s a tricky thing to achieve: a drive for good works without personal ambition. It’s a standard that has eluded me throughout my own work, but one I constantly reference. Dad’s love of people, and his need to make the world better is a thread that runs through almost all of my career decisions.

Dad struggled with the ravages of Alzheimer’s for a long time. The first external signs of it came almost fourteen years ago, he was diagnosed twelve years ago, and lived in a care facility over eight years. When he was able, he and I talked about his fears, and mine, constantly. I loved being his friend and confidante, it was an easy way to repay him for all the great and good things he’d done for me over the years.

Like an acid test for personalities, they say that Alzheimer’s strips away the edifices, your barriers, as it progresses. For Dad, that meant he just became calmer, and more giving as the disease took away his memory. The nursing home staff told me Dad would minister to other patients, holding their hands, sitting with the anxious. Befriending the lonely. “We all love him so much,” each of his nurses said to me in turn.

In a strange quirk, the nurse who admitted him eight years ago, was the one who ministered to his final hours, and pronounced him dead. “He was a great man,” she said to me as I left his room the last time last Sunday night.

Dad loved jazz, played it constantly, and dragged me to Chicago Jazz Fest and Blues Fest performances. He knew the names of obscure drummers and bassists and would regale me of times he’d seen them at the old Jazz Showcase club years ago.

But anyone that knew Dad well, knew him for his piano playing. Eschewing sheet music, he’d play his own songs, a unique one every time, because he claimed, he couldn’t remember anything he’d played before. But wherever he lived, most weekend afternoons, you’d find him at his stand-up piano, starting with a boogie-woogie, then a tune that transformed into a sweeping rhapsody with a repeating leit motif.

His piano playing could come at any time: Waiting for people to put on jackets, venting rage from a terrible Bears game, digesting dinner. The songs were an expression of his emotion and state of being; a way to talk to anyone who could hear.

Like a fingerprint, his music was unique and indescribable. But if you heard it a few times, you’d recognize four or five themes that repeated themselves. Never sad, they always ended up ranging and expansive, drawing you to imagine a vast world of many wonders. After he played for a while, he’d be relaxed, happier, ready for whatever was to come.

There is so much more I would like to tell you about Lou Fourcher. The sound of his walk down the hall, his love of sly humor and his guffaw-like laughter, his love affair with Lake Michigan and bodies of water in general, the natural way he took to a picnic blanket in a patch of grass, like it was the best place in the world, no matter where it might be. His radiant intelligence that was somehow never cutting, but instead managed to fold you in.

I have anticipated writing this memorial essay for years. And to finish it, I feel like I am letting go of him just that much more. Feeling the beauty and love that was my father, slip away from me.

It is so hard to stop writing.

Sitting at his piano bench, playing that piano with the funky A key he could never get fixed, is how I’ll remember Dad forever. I am so grateful he was my father.

—

If you read this in time, and remember him, please join us at his open memorial service, Sunday, January 27 at 2:30 p.m., at The First Unitarian Church of Chicago, 5650 S. Woodlawn Ave. Dad was also a huge fan of Ruth Rothstein, with whom he worked to help make Erie Family Health Center one of first health centers to apply Medicaid funding to treating AIDS patients. So, in lieu of flowers, please consider making a contribution to The CORE Foundation, 312-572-4549, 2020 W. Harrison St., Chicago, IL 60624, which benefits the Ruth M. Rothstein CORE Center, a clinic that focuses on the prevention, care and research of HIV/AIDS and other infectious diseases.