It’s late August, which reminds me that I was not a very good carpenter. I had trouble making joints square.

That would seem like a very simple thing to do: Measure twice, cut once – and when you cut, cut carefully. But seventeen year old me had trouble doing those things. I was unfocused, and frankly terrified of being found out that I wasn’t really very good, so I rushed even more, which is something a good tradesman should never do, and my work got worse and worse.

By that measure: My worth as an aspiring stage carpenter in the summer of 1990, when I was seventeen, should have been a terrible experience. But the reality was, in between the awful, non-square set pieces, I managed to have a pretty good summer.

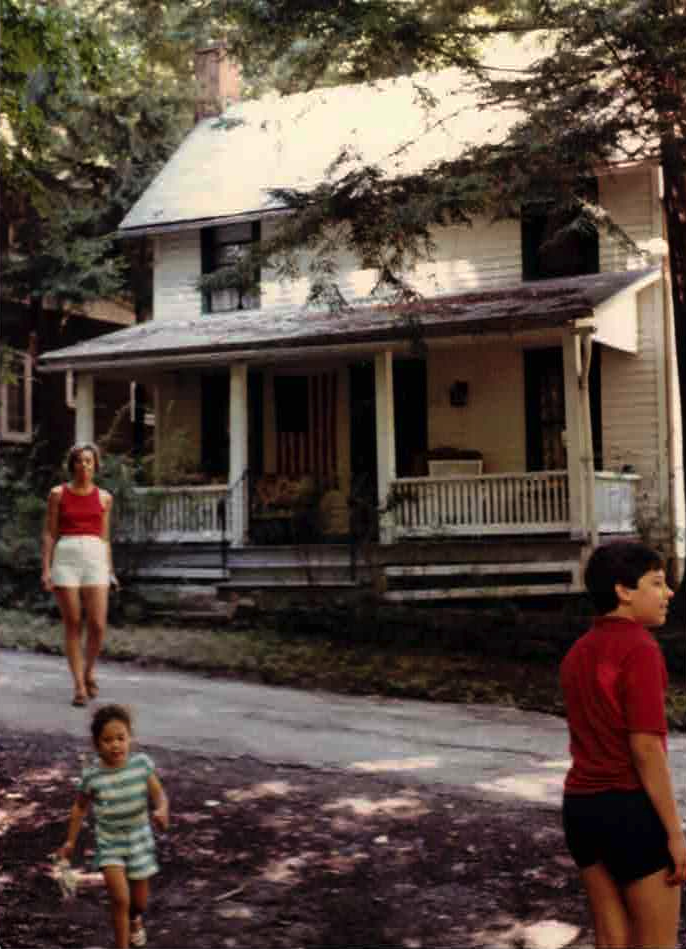

For decades, my mother’s family had been going to Western New York, to spend summers, or part of them, in Chautauqua, this crazy, amazing, Waspy, tolerant, straight-jacketed place set on a long lake, that’s equidistant from Erie, Pennsylvania and Buffalo. At least when I went in the 80’s, there were no good places to go – no movie theaters, grocery stores, amusement parks, or anything – nearby Chautauqua, so once you got there, that was it. You made what you could of your time there.

And depending on your age, it could be a wondrous place, or dull as dirt. In elementary school, it was a blast. It’s a giant, fenced-in town, patrolled – even in the 80’s – by cops on bikes and restrictions on cars, so children were allowed to roam the whole town willy nilly. It included a forest with a creek, a long lakeshore with beaches, an old fashioned-ey ice cream parlor, a cheap movie theater with matinees, and street after street of old victorian homes crammed next to each other in a dense configuration that made no sense when you’re so far away from any urban setting – except this artificial one.

Families rarely stayed for a whole nine week season, they usually just rented a place for a week or two – the lucky ones for a month or longer in a house owned by grandparents. So, kids constantly cycled in and out. You’d go to the day camp in the morning, which usually included swimming in the frigid lake, kickball or some kind of game with running, and then an arts and craft. You’d jump on a bike – even at seven or eight – and bike home for lunch, and then in the afternoon either pester your parents for something to do or be shunted out onto the street to go find other kids to play with.

That was never a problem, since there were usually a standard set of four or five places to find other kids: The ball field by camp, the rec center, which had video games, bumper pool, and frozen Snickers for sale, the town square, which held the general store, bookstore and afore mentioned ice cream spot, or a beach down by the lake. Most kids were in town for only a week or two, so that meant friendships were loose and always open to new kids. Of course, there were the kids that stayed for a month or longer – usually they formed cliques of their own, since you weren’t part of their in jokes and knowing smiles.

Instead, kid summers at Chautauqua were like brief hookups: If you found a cool kid or two to hang with one afternoon, it wasn’t likely they’d be around the next day. Not only was there the danger of them leaving town, there was also the chance they’d go on a family day trip to Corning or something like that. You had to make of it what you could, and usually that meant playing in the creek, biking around aimlessly, convincing your parents to give you money for frozen snickers, or maybe getting into a pickup game of kickball at the ball field.

As I got older, I discovered what Chautauqua was really about, which was learning, intellectual, artistic, and spiritual discovery. Although the place has about nine churches and a synagogue, the spiritual part never resonated with me, but the intellectual and arts part did. Twice every weekday it hosts giant outdoor lectures for seating for thousands, where I saw – and shook hands – with people like Taylor Branch, Al Gore, and Maya Angelou. I took computer classes and learned how to program Basic, went to film study classes with my stepfather about early talkie comedies, and sat in on literature classes with my grandmother, who lived for that kind of thing.

The arts really took a hold on me. There were free symphony concerts just about every other night, which you could walk over to, slide into a bench, listen, and if it didn’t appeal, slide out and go for a walk along the lake. The town hosted a massive arts school, with summer stock ballet, theater, opera, and multiple student orchestras. Part of the town has a field with dozens of little practice sheds. You could walk through it on an afternoon, and catch notes from a practicing opera singer, oboist, or brass trio trying to get it just right.

That meant there were tons of cheap theater, dance, and opera performances to see. My mother and stepfather, already denizens of Chicago’s symphony and opera, pushed me to go, and when I did, even at ten and eleven years old, I was captivated, especially by theater and opera. Here were giant productions that attempted to surround you with sound, movement, and visuals – live! – to transport you to a different place or idea. If you let yourself go, you could actually move your mind to some other location and leave yourself behind.

I loved it.

Back home, I had a stepsister on my father’s side of the family that was becoming a professional actress. So, maybe the theater thing could be for me too, I thought. In high school I acted in plays and sang in chorus, and while I wasn’t bad at acting, I couldn’t memorize lines – to the point where sometimes I improved scenes, which really didn’t work well when everyone else had memorized their lines.

So, I drifted to technical theater and got fairly decent at designing and operating lighting and sets – for a high schooler.

Even now I’m not sure if my teachers – genuinely talented Chicago scenic designers who taught high schoolers during the day for the health insurance, and worked on real stages at night – honestly thought I was good, or were just shining me on. But I got a lot of encouragement from them, and felt like I was learning things. So, eventually I thought: Maybe I could combine technical theater work with being in Chautauqua? I applied for and won a job as a stage carpenter in the summer stock theater, which made me, at seventeen, the youngest person there by at least two years, while most of the actors and crew were well over drinking age. I had a ton to prove.

I proved myself to be terrible.

There were the times I made so many bad cuts we ran out of lumber. A doubly bad problem because I didn’t have a driver’s license, I couldn’t go get more. I say “times” because this happened more than twice. Or thrice.

The times I split wood because I didn’t use the right kind of nail, or drove it in too hard, or the spattered paint jobs, or the unsquare blocks I built.

They couldn’t fire me because it was summer stock, and everything would be over in a few weeks anyway. So I became dumb labor, hauling stuff, hammering big nails, painting primer coats, which there is plenty to do in a theater, so that was okay, but still. Everyone knew: I was the kid that couldn’t do jack.

But still, there was so much else going on that summer. The arts students and workers, like me, were put up in a series of ramshackle Victorian rooming houses across town. Built originally for spiritual pilgrims to the many churches, after decades of ecclesiatic use they’d fallen into disrepair and were converted into housing for the unwashed. Thirty or so lived in a house, doubling up in tiny bedrooms, four or five surrounding a common room with a hot plate kitchen and a two-showered bathroom with curtains that never seemed to close all the way. It was a rathole full of libertine arts people, so there was tons of drinking, pot smoking, and sex.

Seventeen year old me was excited to be among such fun adults, yet I couldn’t process it all. My housemates all seemed to get this, called me “The Kid”, and purposefully left me out of the big weed smoking sessions, and much more late night activity. I acted upset, but was internally grateful: I had no idea how to handle this grown up stuff. Better to pass on it for now.

Yet, I lived in the arts worker house, which meant to the outside, I was more grown up than just seventeen. Rather than paying to be in the Chautauqua arts community, Chautauqua was paying me, which was a kind of badge of honor among the many students there, which ranged from sixteen year olds in a summer orchestra, to post-college students paying tuition for a summer of training with opera great Maria Callas.

As part of the arts program, we workers got free food in the arts school’s cafeteria across town, and because we spent the day swinging hammers, we were usually pretty hungry. Before eight each morning, me, my tech theater roommate, and a gaggle of opera singers would get our bikes, wipe the morning dew off our seats, and ride past rows of sleepy gingerbread houses. We’d saunter into the cafeteria, my roommate and I in paint-spattered shorts that announced “tech crew”, and the singers nattering away in three or four languages like only opera singers can do.

The crowds of dancers, actors, and musicians moved aside for us. We imagined it was because we were so brawny, but likely it was because we were the uncouth: tech and opera people. I know that sounds like a strange brew, I mean theater tech people are very obviously strange. But opera?

But then, have you ever really talked to an opera singer? They are intense, usually multilingual, cultural sponges, that are many times more emotional about life than even actors. For most of the world, this is too much to endure. But tech theater people are built to endure, so we kinda liked the opera people. One guy, with an incredible baritone, had memorized all of Don Henley’s “End of Innocence” album, which was big that summer, and would sing it operatic style at the top of his lungs during odd times of the day. Another guy, some kind of bearded South American who always wore a silk scarf, would insist on speaking Italian and French with his compatriots to improve his speaking.

Here I’d be, riding my bike to the cafeteria, with one dude doing operatic Don Henley, and another nattering away in Italian. We’d ride casually, not paying attention to our surroundings, as you might if there were no cars around. Then, one day we rode through a stop sign without stopping. From behind a bush, a Chautauqua bike cop blazed out at us, “Halt, in the name of the law!”

He began dressing us down for ignoring signage, and seventeen year old me, disassembled, terrified of a cop pulling out his ticket book, writing me up for a bike traffic infraction. But my opera buddies, who each maybe had ten years on me, looked at one another and began yelling in Italian, pointing at things. The Chautauqua bike cop had no idea what to do, as the opera guys gesticulated more and more wildly, with more than a tint of righteous anger.

“What are they saying?” he pleaded with me.

“I have no idea. They don’t speak English,” I gamely interpreted.

The bike cop lost his stern attitude, gave up, and waved us on. We’d avoided a fifteen dollar ticket.

This story was told and retold again – mostly by us – to all the summer arts crew, as evidence of our badassness. A bike cop! From behind a bush! Nothing could stop us. We were giants among the summer stock.

And here, feeling myself among the greats – despite the fact that I couldn’t build anything square – I found myself with my first real girlfriend. She was a high school kid, like me, but in a summer acting program, one of those people who thought “Phantom of The Opera” was terrific, and emphasized her love of drama by speaking with a sort of Mid Atlantic accent, which slipped into British-isms now and then. Of course she was silly, but so was I in my paint-spattered shorts and faux blue collarisms.

We were both playing roles that summer, and both of us wanted to play boyfriend-girlfriend, we didn’t really care with whom. That whole summer, despite all the kissy-face we made, I don’t think we ever really looked at who the other person was, we were so glad to have a “relationship”.

Finding a summer girlfriend only elevated me in the eyes of my older housemates, who were all rutting away trying to find someone else to rut with them. They’d pair off now and then, but they were older, true artists, so things were so much more complicated, they’d complain. I was young and clueless, so it was easier, they told me, and I suppose there was truth in that.

For the summer I’d earned a real paycheck – despite being terrible at my job – lived on my own, gotten a girlfriend, and evaded the bike cops. I went on dates, got sweaty at work and showered before dinner, had to manage my finances. Except for a brief two weeks, my parents weren’t around, and so my choices were my own. It was like adulting with training wheels.

Inside, I still cringe from being such a bad carpenter – and for dating a girl with a fake British accent. But everyone was so good to me as I bumped along, trying to figure out how to be responsible. Those few months, I’m not sure there could have been a better place for me in the world.

Eventually the summer stock season came to a close. We’d built sets and ran tech for five shows in ten weeks, a crazy pace really. It was getting cooler in the late August nights, and my housemates began peeling off to head to fall theater jobs or early college starts. I said goodbyes, traded a few addresses with promises to write and visit, and had a teary, mutual breakup with the accented actress.

I don’t remember who gave me a ride to Buffalo airport so I could fly home, but I remember getting to my plane, sitting in my seat, and feeling bigger and more sure of myself than I’d ever been.

Going back to high school seemed like a step backward. But there was just one year to go before I went to college and really started doing the real grown up thing.

I was ready now, even though I couldn’t make a joint square.