When I started French classes in middle school, I was immediately fascinated by the nature of my last name, Fourcher, which seems to be derivative of fourchette, the French word for “fork”. It’s a far from common name in the Midwest, where I grew up.

Although my father, Louis A. Fourcher, was born and raised in Fairhaven, Massachusetts, the least French place in the world, my grandfather Charles was originally from Augusta, Georgia, raised by his father Louis H. Fourcher. Also, not very French.

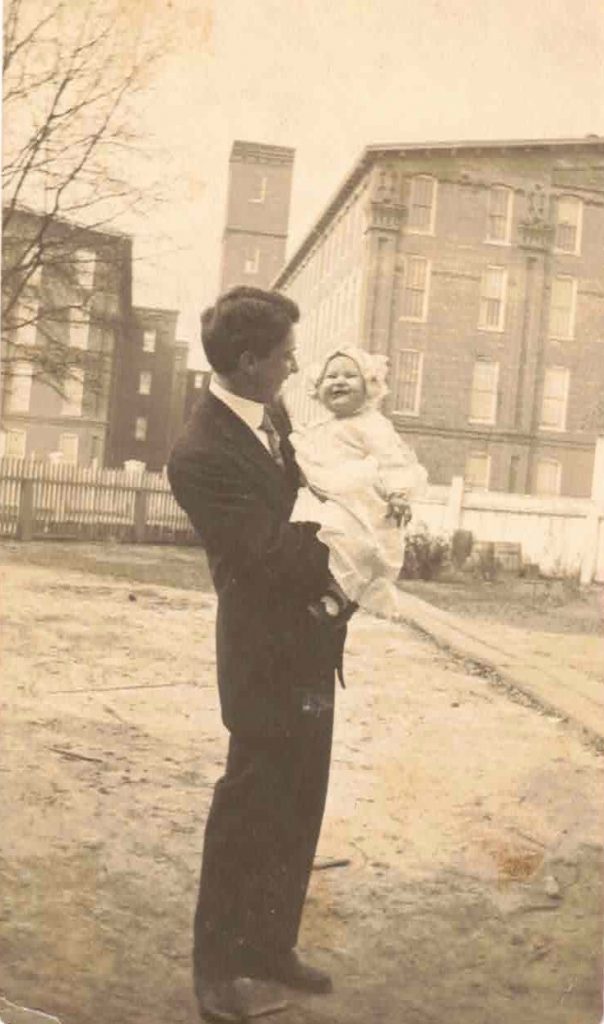

Wondering what we were all about and why we had this funny last name, growing up I constantly plied my grandfather for family history. He had a lot of it, with hundreds of old photographs, letters, a whaling ship diary, and bibles with family trees written in the front pages.

It’s a treasure trove of history, but because my grandfather never pressed his elders for their stories when he was young, the linkages between pictures and what he knew of the Fourcher family was patchy. So, I set out on my own to learn what I could.

The big things I knew about my family were recent, and I’ve written about before. Like my father’s civil rights activism in the South and Chicago. Like my mother and her father (and my dad) marching with Martin Luther King in 1962.

This was heady stuff for a kid, putting my family on the side of the light. We were a family that aligned with the mistreated and maligned, and worked to ensure those wrongs were made right.

This kind of thinking made me a self-righteous kid, growing up.

But by the time I got to my mid-twenties, the gaps in my grandfather’s memory puzzled me. And a recent trip my stepfather Bob took to his ancestral hometown in Spain snagged something in my mind: Everyone in the town looked and gestured like him, my mother reported from the trip. “It was like going to a town full of Bobs,” she said. I wondered if there was a place somewhere full of people that looked and gestured like me.

So, blessed with a few months of unemployment in Washington, D.C. between a job ending and the start of graduate school in 2001, I set upon the National Archives to see what I could learn from whatever records I could find there.

Tracing back through census records from Augusta, I learned my grandfather’s grandfather, Victor, also ended up in Augusta, and that he’d started his gun, lock, and bike shop there sometime in the late 19th century. Also, that Victor had an older brother, James, a bricklayer who never married or had kids, and seemed to live with Victor until his death.

Looking further back, I found in the 1860 and 1850 censuses that Victor and James “Fouche” had been residents at the Charleston Orphan House. I ordered some records from the Charleston County Public Library and learned the boys had been dropped off in 1844 by a Susan Fouche from Pennsylvania. As much as I looked, I couldn’t find a Susan Fouche anywhere in any other census records, in Pennsylvania or otherwise.

In 1861, Victor and James would be 20 and 22, respectively. So, on a hunch, I looked in the Archives Confederate Army records. There I found the brothers, some of the first enlisted in the First South Carolina Volunteer Regiment of the Confederate Army. It was the very first Confederate unit to form, just days after the bombing of Fort Sumter.

I felt the scales falling from my eyes.

Their regiment’s muster records showed the brothers – with Victor serving as a drummer in the early fights – then later in Antietam, the second battle of Bull Run, and just a couple hours of marching away from being in Pickett’s charge at Gettysburg. Eventually they were captured and spent two years interned at Fort Key in Baltimore. On their release, they were required to sign an oath of loyalty to the United States. I found Victor’s written oath and signature in the Archive’s microfiche.

Wondering if I could find more about Fouche, or Fourcher, or whatever, I searched archives across the South. There are plenty of Fouches in Southwest South Carolina, but few of any repute. But there are also many in Louisiana, mostly in New Orleans, where I found in the city archives many “Fourche” members of the state legislature, at least one Congressman, a street in Uptown, and then the extensive Fourche plantation on Mississippi River, which is now the site of the Audubon Zoo, in New Orleans. These were leading, stalwart supporters of slaveholding society, enslavers to the last.

What I learned exhausted me. My frenzy of research over the summer of 2001 forced me to reconsider what my family was about. Since my grandfather was still alive – and now into his nineties – I visited Massachusetts to ask him about everything I’d learned.

It was all news to him. Nobody in the family had ever talked about the Civil War, slavery, or plantations. He’d lived in Augusta until he was 7, when practically the whole city burned down in the Great Fire of 1916. That led to my great grandfather decamping for New Bedford, Massachusetts, where new cotton mills were growing, and men with cotton experience were needed. James had passed by then, and Victor had died in 1914, before the family gun, lock, and bike store was lost in the fire.

When the Fourchers moved up North (nobody knows when the extra “r” was added), apparently everything about Southern history was left behind, buried with the Confederate veterans. Once he moved North, my grandfather never visited Augusta, or anywhere in the South until he went on a Princess Cruise out of Florida in the 1970’s.

Mostly growing up in lily-white New Bedford, the most my grandfather knew about the South was from an ancient picture he kept of a Black woman he still held dear in his heart, 86 years later, his “Mammie”, who mostly raised him for the first five years of his life, he told me. Once the Fourchers moved, Mammie was left behind, nameless, and without any knowledge of her life, wants, and hopes. That picture, except for my memory of it, is now lost to time.

I too had grown up with a Black caretaker from the South, Inez Fleming. While her personal story is complicated – I’ve written about it elsewhere – the important part is that I knew her story and she was still very much part of my life in my late twenties, so it perplexed me that my grandfather and I had this thing in common, and yet his ending with Mammie was so cold. How could you have such an important person in your childhood, only to dispose of her?

I tried asking my grandfather about this, but by this time he was a nonagenarian and his tolerance for things he didn’t want to discuss was pretty low. Although the discussion might have been helpful for me, I’m sure there was little good from his perspective.

What I now know about my Southern family is sobering. Slaveholders, some of the most strident Confederate soldiers, unthinking about Black people as people or anyone that might have their own cares and desires.

I would guess that most of White American history is so complicated. If we weren’t participating, we were complicit with slavery. Or at least we ignored it. And then Black Americans were just plain ignored, even those who touched our lives.

The stain and pain of American chattel slavery is deep and complex. I suspect that for most White Americans, the knowledge that their bloodline may be connected to slavery would be a difficult burden to bear. It is for me! And I didn’t even look into the specific acts my ancestors might have carried out, like beatings, rapings, capturing freed slaves, or whatever horrible things happened.

Just the knowledge that they are likely is upsetting enough – and that I am connected to them.

Yes, we’re not responsible for the sins of our fathers. Yet the consistent economic and social inequities between Black and White Americans suggests there is some reconciliation still due.

Maybe you’ve heard someone say, “But my family wasn’t responsible!”

And to that I ask, how are you so sure? After a few days of digging, I found incontrovertible proof that my ancestors were responsible for promoting slavery. What would a few days of digging reveal to you? And what sorts of things did your ancestors do that wouldn’t be recorded?

The truth, I suspect, is that we’re all mixed up in it and that there are no clean bloodlines. American history is soaked in the blood of slavery and deep down, every single white person knows it.

I suspect the weight of that knowledge, the active responsibility our ancestors, along with the clear inequities between Black and White people in the United States aggravates us all. Whites, because we know we’re getting away with something, and Blacks because something has been taken away.

There’s been a growing amount of talk about the need for reparations. A California state-appointed task force is expected to issue a report later this month that will likely call for billions of dollars of direct payments to Black Americans descended from slaves. That seems like a step in the right direction, but anyone who’s seen HBO’s Watchmen, can envision a world made worse by reparation payments.

We all need a first step – a consideration of our families’ roles, and a consideration of our own roles in ignoring our past of slavery and Black oppression. The role our families played could have been active, like the Fourche family’s, or a passive denial, which allowed more aggressive behavior to go unchecked. It’s time to own up our mistakes.

Happy Juneteenth, White America. It’s a good time for personal reconciliation.