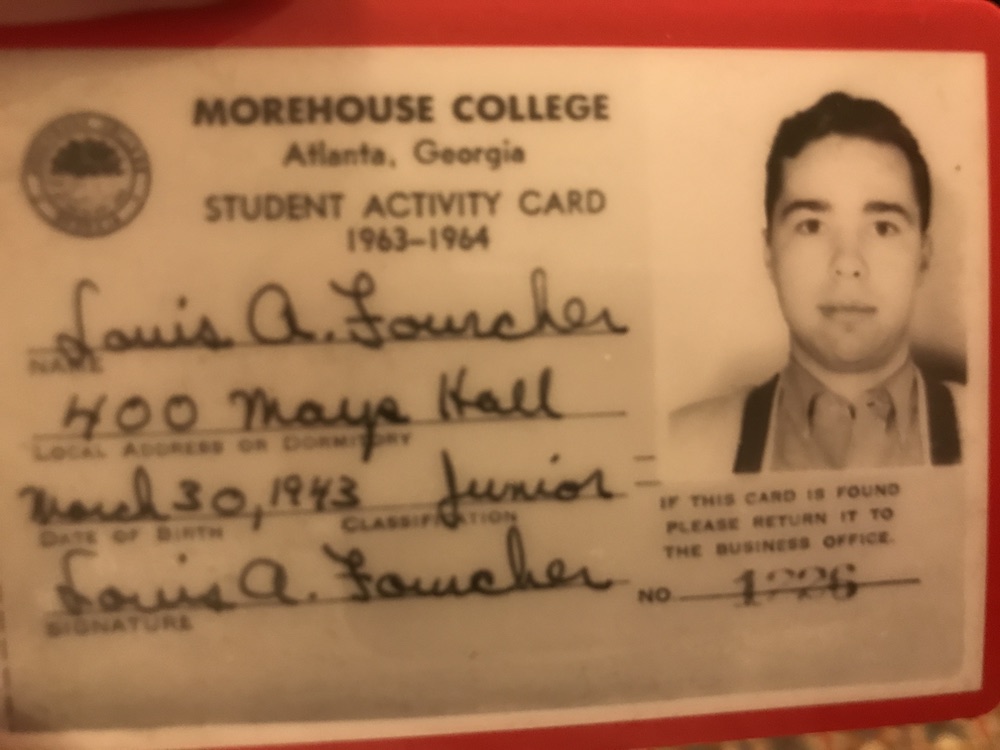

Far, far in the back, there’s Lou Fourcher.

Last month my father, Lou Fourcher, passed away after a fourteen-year struggle with Alzheimer’s. Since then, our family has been going through old papers and photos, rekindling our memories of him. Last week, my aunt, Charlene, found a printed copy of this old email exchange between my father and his niece, my cousin, Abby, who was working on a high school report on the Civil Rights Movement in 2001.

From a small New England town and the first in his family to go to college in 1961, my dad was quickly swept up by the civil rights movement. Although he was far from important, he was one of thousands who participated. Dad response to Abby’s questions remind me of ha many war veterans talk about their war experience – I was just one of many, it was no big deal compared to others. And yet, there he was, doing his part.

Dad was incredibly modest, throughout his entire life. It is as remarkable to read how much he downplayed his role, as it is to understand how far he pushed himself to live in the shoes of others.

Abby, although she was just sixteen or so, asked some really good questions. I’ve made a couple grammatical fixes, but most of what’s here is how he wrote, eighteen years ago, about his experience.

Subj: Civil Rights Movement Interview

Date: 1/14/2001 11:55:53 PM EST

From: Fishy333

To: LAFOURCHER

Hi Uncle Lou,

How are you? I’m pretty well. Anyway, thank you for agreeing to do this. My assignment is to interview someone who lived through an important event in U.S. history, such as the Civil Rights Movement. Mom told me that you were involved with the Civil Rights Movement, so I figured that you would be an excellent person to interview. I will list my questions below and you may answer them whenever you have time. Feel free to omit any questions that you don’t know or don’t want to answer, but for those that you do answer, please write as much as youcan.

Thank you,

Abby

1. What made you decide to become active in the Civil Rights Movement? Was there something that happened or someone that influenced you in particular?

I don’t think I was ever an “activist” in the Civil Rights Movement. However, there were some early experiences that probably helped me to be tolerant and curious about people who were not “white .” My parents, despite the old prejudices of their pasts, were certainly accepting of the very few black playmates I had. Then there was Jerry, an older Jewish kid on our block (he was probably 16 at the time); I remember hearing him telling a couple of us – with anger and tears – how local business people wouldn’t hire him for summer work because he was Jewish. That affected me. Sometime in 1960-61, when I was in high school, there was young African-American man (Rev. Woody White) who had come to our church in New Bedford to be the “Assistant Minister.” He was studying theology in Boston and would come down on weekends. I guess he was the “youth” minister. He won over the group of teens at church pretty well. But one day he said that he and a fellow student were going to picket (or sit-in if possible) at the local Woolworth’s in New Bedford – todemonstrate solidarity with the people who were sitting in stores and lunch counters across the South. He invited all of us in the youth group to join him the following Saturday. I really wanted tojoinhim but I had to ask my parents.Of course, they had heard the news reports from theSouth; they were scared, they thought it might be dangerous, and there were those old prejudices.We argued – I argued – a lot;it was probably the worst disagreement we had had. It changed me. But I was a church-going “good” kid and I obeyed my parents. As it turned out none of the other kids wenteither.

Perhaps as a way of compensating for my non-participation in the Woolworth’s demonstration, I began to think about organizing – again through the church (and with Woody’s support) – a kind of conference on civil rights and racial tolerance. joined with another teenager, David (from another church), and an old and wise minister and leader of the local “interfaith council.” Together we managed to get several hundred teen-agers – Protestants, Catholics and Jews in an auditorium to listen to mostly adults talk about race. It was a pretty good event – lots of good talk.

Perhaps as a way of compensating for my non-participation in the Woolworth’s demonstration, I began to think about organizing – again through the church (and with Woody’s support) – a kind of conference on civil rights and racial tolerance. joined with another teenager, David (from another church), and an old and wise minister and leader of the local “interfaith council.” Together we managed to get several hundred teen-agers – Protestants, Catholics and Jews in an auditorium to listen to mostly adults talk about race. It was a pretty good event – lots of good talk.

2. (I switched this question to keep the chronology straight.) Mom also mentioned that you participated in the March on Washington. When did this occur? What was it like? Who did you go with? What did you hope to accomplish by participating in it? Do you think that you did accomplish your hopes? How does it feel to have participated in such a significant event of U.S. history? Did you hear Martin Luther King’s speech? What was listening to his voice like? Did it influence you? How?

At the end of my sophomore year in college (Bowdoin), I was looking for something “different” to do that summer (1963). I volunteered for a job working with “inner city kids” in New Haven, CT, under the auspices of a big old Episcopal Church. I was not a great “youth worker” but I learned a lot. Much of my time was spent with Black kids living in the local public housing – not far from Yale. There were gang fights that I would hear about the next day; there was lots of tension between Blacks and Italians – the old Italian neighborhood was shrinking… The church had a basketball team that was quite famous – they had won something like their last 40 games. Their coach was this very earthy Italian guy who gained the respect of these young black guys most of whom lived in the “projects.” But for some reason, when I arrived he decided to quit. It became my job to take over the team though I knew nothing about coaching basketball. I was not popular with the team. Nevertheless, a game was scheduled with a very tough team on the lower East Side of New York . I drove someone’s Volkswagen bus and the assistant pastor at the church drove the remainder of the team as we tried to find our way to a blacktopped basketball court somewhere on the East Side. We did; I tried to be coach-like, but the older guys on the team knew better what to do; so I mostly cheered them on. The team lost its first game in years… [The New York team came up to New Haven several months later…and we won.] At the end of the summer, the head pastor (Priest?), who was very active in civil rights, asked me to join a large New Haven group who were going to “March On Washington.” We went by train – it was dubbed the “Freedom Train.” On it were hundreds of people, just a few of whom I had met in passing during the summer. In our car was William Sloan Coffin, a pretty famous minister-activist who was the Chaplain at Yale. It was my first trip to D.C. It was very hot; and there were lots of people; and it was very exciting. I ended up with some of the people from New Haven that I had met, but we were a long, long way from the Lincoln Memorial (which is where I think the speeches were made (but maybe it was the Capital steps…). I do remember being moved by King’s speech (over loudspeakers in the trees of the Washington Monument park). There was certainly a sense of history being made that day, but I was probably more overwhelmed with the size and momentousness of the event than I wasinspired.

I had arranged that on the train back to New Haven I would get off in Penn Station in New York City to go to a conference on Religion and the Arts at Columbia (arranged for me again by the Pastor in New Haven). I mention this because at the conference there were two Black students at Morehouse College in Atlanta who had met some Bowdoin students who had visited for a couple of weeks. They talked about setting up a real exchange of students between the two colleges. This interestedme.

3. Mom mentioned that you attended Morehouse College, an all-Black school, for one semester as an exchange student. Where is Morehouse College located? What year did you attend this school? How was this school different from all-White schools? Which school did you like better? How did the other Morehouse students treat you? What was it like when you returned from Morehouse to your regular school? Were you ridiculed by anyone when they learned you were going to spend a semester at Morehouse? How did your experience at Morehouse influence you?

In the Fall of 1963 there was a whole process of applying to be an exchange student at Morehouse (not very many people applied…). I was very pleased to be accepted (and my parents were supportive). Unlike Bowdoin, Morehouse was on a Quarter system; so I got to be a student there for two ten week terms from January to June of 1964. Morehouse was, like Bowdoin at the time, an all men’s liberal arts school attended largely by middle class students. Unlike Bowdoin it was surrounded by several inter-related schools – including the women’s school, Spellman College. The facilities were not as good as Bowdoin’s; there was less money. But there were some very good teachers. One especially, Mr. Campbell (who taught Shakespeare and took groups of us to movies that we later critiqued) had a great effect on me. The place, in many ways, was in the center of civil rights activities. M.L King, Jr. preached at his father’s church which was a walking distance from the school. King senior was on the Board of the School. Its President at the time was Benjamin E. Mays). I did get to hear King preach a couple of times; I met a young activist (perhaps 2 or 3 years past his graduation from Morehouse), John Lewis, who has been a Congressman from Atlanta for quite a few years. He was famous for being in the think of many sit-ins, demonstrations, etc. Julian Bond. another Morehouse graduate who later became mayor of Atlanta, spoke to us a couple of times. But most impressive were the SNCC (Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee) people who we met and learned from as we joined them on several demonstrations in Downtown Atlanta. Like John Lewis they were the real activists – in Atlanta and across the south. Imagine these very preppy looking white guys from New England, standing on a sidewalk in downtown Atlanta getting taught to hold tight to your fellow demonstrators’ hands in order to avoid the powerful shock of the cattle prods used by restaurant and store owners (and police I think) to discourage sit-in demonstrators. I never got shocked – we usually left the restaurant when the police were called.

Atlanta was going through incredible change. There were integrated restaurants popping up all over, but there were still plenty of segregated places. There was this one segregated restaurant, a very famous place in one of Atlanta’s neighborhoods. It was run by Lester Maddox who was famous for having a weekly “advertisement” in the Atlanta Constitution newspaper that really was a vehicle for him to comment (negatively) on the civil rights movement, promote segregationist ideas, and generally comment on politics. Early one weekend morning several of us, both Bowdoin and Morehouse students, had been told that there was going to be an attempt to demonstrate at many restaurants simultaneously at once around the city that very day. Actually, our information was bogus, there were no other demonstrations. Nevertheless, about eight of us decided that we would go to Lester Maddox’s famous fried chicken restaurant. We went in two cars – the drivers (wisely, it turned out) stayed in the cars; the rest of us went to the main door – but got no further. There was immediately lots of yelling and threats. Mr. Maddox was giving orders. The black help at the restaurant seemed to be pretty well versed in what to do with demonstrators – out came these wooden axe handles – yes, axe handles (big axe handles). We stupidly kept standing there saying we wanted to eat… Then there was this old maid on a balcony across the street yelling out something like “Go get ’em Lester, get those “nigger lovers.” By then we were already backing off and yelling to the drivers of the cars – the restaurant guys were bringing out a big fire hose and one (at least) picked up a brick (and threw it and more) as we retreated to the cars – flying around the parking lot with doors open and us trying to get away…One thing we learned that day – civil disobedience is a serious thing – not a game. I think it was in the early 70’s that Lester Maddox became governor of Georgia.

I never really was able to express what I felt during those times. Later I kind of expressed it with my actions. Otherwise, I’ve pretty been inarticulate about the feelings that I must have had, and the things I saw in Atlanta, the transportation system was pretty much officially integrated, but most white people still sat in the front of the bus. On my first bus ride there I went to the back of the bus – no big deal for the black people sitting there, but I felt like I crossed over some very strange boundary). Well there’s a memory I haven’t had since then!

4. Did you participate in any sit-ins? Where? When? Were you afraid that you might be arrested? Did you know anyone who was arrested? Were you afraid you might be hurt? Can you tell me anything else about thesit-ins?

I sort of answered this above, but… yes, I was pretty much afraid at each demonstration (though I never thought my life was in danger (accept maybe at Lester Maddox’s place). I participated probably in five demonstrations while there. Though I must admit I was pretty self-conscious at this very nice downtown “integrated” restaurant – whenever a mixed group of us would enter it, the place would go silent for a fewminutes…

5. What other kinds of protests did you participate in? How did you feel when you protested? Scared? Nervous? Powerful? Benevolent?

I participated, but, again, I wasn’t really an activist – I just learned a lot.

6. Does your experience during the Civil Rights Movement still affect you today? Do things that happen around the world today remind you that time? How does it make youfeel?

Yes, it has affected me and how I think. I was the clinical director of a mental health center in Skokie, Illinois which has a very much white population about 35% of which is Jewish. Our staff make-up reflected the population (though not our clientele). I felt good about hiring the first black person to thestaff.

Later I was the Executive Director of a Community Health Center [Ed. Note: Erie Family Health Center] (several sites) in a largely Hispanic community – actually there were several communities – some largely of Mexican descent; then there was a large Puerto Rican population as well as many different nationalities from Central America.I felt very good about working well with various community groups, opened our facilities up for community meetings, etc. Because we were concerned about AIDS in these populations, we joined with a new community organization to form a the “Hispanic AIDS Network” which did HIV education and preventive work on the streets (especially with drug addicts). I was proud to be the Treasurer of thatorganization.

Then there were clashes between Hispanic and black gangs on the West Side – they would have battles in Humboldt Park – the blacks came from the south of the park and Hispanics from the north. Our clinic site – the “Humboldt Park Health Center” – was on the north end of the park and it was dominated by Hispanic patients and Hispanic staff. Black mothers were afraid to bring their kids to the clinic because they would have to cross a (symbolic) boundary. I got some of our staff to start planning a new “satellite” clinic in south Humboldt Park. We hired black staff, and finally got space in a school. It still functions.

7. Do you think that the U.S. has pretty much dissolved racial discrimination since the Civil Rights Movement? If no, where do you most often see racial discrimination? What do you think can be done to eliminate racial discrimination?

I think there is still plenty of discrimination. But the worst of it is experienced by poor people. Middle class people are discriminated against (there are still plenty of scared, ignorant people who will respond to people they know little about with stereotypes and anger). But black people (and to a great extent Hispanics) in cities deal with a state of poverty that has evolved over many years in which for example, many jobs were lost because of the closing down of large unionized industrial companies (i.e., good paying blue collar jobs) and economically integrated neighborhoods were destroyed because of the process of integration which brought middle-class blacks out of the poor neighborhoods – leaving them all the poorer. This is the case in Chicago and several of the old “rust belt” cities. So, in some neighborhoods there are huge numbers of young (teen age) single mothers, kids still in gangs, many young men in jail for drug offenses, crummy schools, and some neighborhood that are so poor that the local McDonald’s can’t survive. I worked as director of another community health center in such a poor community [Ed. Note: New City Health Center, in Englewood] – it wasn’t really a community – it was a place where I might see (out of my second story office window) a young boy on a bike at noon time, stop for a moment, take aim with a large pistol, fire it at some other kid down the street and then disappear down an alley…

8. Is there anything that you wish you had or hadn’t done during that time? What would you have done differently?

I wish I had paid attention more. Much, much more happened in New Haven or Atlanta – or even on the west side of Chicago – when I was around, but I was often paying attention to the small stuff – what movie to go to, watching the 10- o’clock news, etc…l didn’t really understand that the news was happening around me.

9. How did the Civil Rights Movement affect you overall? Who or what was the most influential part of the Civil Rights Movement in your opinion? Why?

Perhaps it was my age (around 13), but Jerry’s tears and anger at not being hired for a summer job because he was Jewish has stuck with me as much as any events since. The “Movement” for me was some of the people I met and respected. I think it led me to choosing the various community health care jobs that I’ve had over the years in Chicago.

10. Please write anything that you can think of pertaining to the Civil Rights Movement that I have leftout.

You asked some good questions. I think l’ve waxed a little biographical, but I hope some of the historical stuff is useful.

Well, that’s it! Sorry for any misspelled words or unclear questions. I appreciate you taking the time to write as much as you can. Thank you once again.

Thanks for asking. It was fun!

[Final Note: Incidentally, my mother, Barbara Ireland, and her father Paul, were at the March too, but Barbara and Lou were not to meet for another two years.]