It begins one of two ways, either a call to your cell marked “No Caller ID”, or from that gut-wrenching number from the nurse’s station you’ve memorized.

“Hi, Mike. There’s no emergency with your dad. I just wanted to check in on some things.”

These kinds of phone calls are never good, but they’re better than the alternative, when there is an actual emergency.

“So, we haven’t talked in a bit. But have you taken care of funeral arrangements?”

That isn’t exactly what the social worker said, in fact he never said the word “funeral”. Instead, he said something artful and sympathetic, so you understood the topic without an overt mention of death. But still. The dull pain hits you.

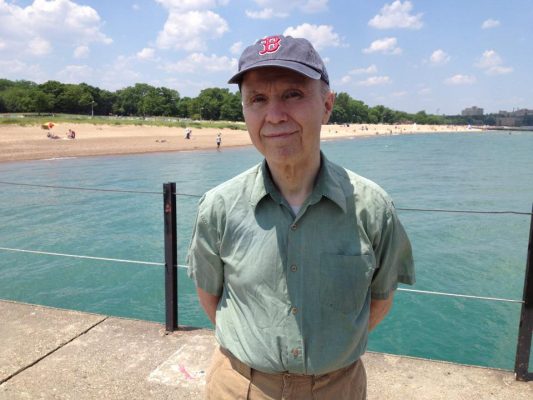

My father, who has been living with Alzheimer’s for twelve years, well, at least since he was diagnosed, is in a nursing home here in Chicago. He isn’t married, and I have no brothers and sisters, so all the calls, all the paperwork comes to me.

And yes, I’m the main one who visits him too, although over the last couple of years I’m ashamed to admit, the visits aren’t that often. But also in the last couple of years he’s been a total vegetable, so I don’t feel like I’m really hurting anyone.

Well, I do feel bad about it, actually. But it’s so complicated. I mean, he’s totally gone now. The details of his current illness are ugly, and my father’s modesty and propriety keeps me from describing how bad things are. So, please take my word for it: He is a shell now. None of the man I, or anyone else once knew, is there.

Gone, all gone. Except for the shell of a being that looks like a person. Except it really isn’t.

And so now, and for the last couple of years, I’ve been responsible for someone that’s really not there anymore. I could tell you all kinds of things about how wonderful a man he was, how loved he was, and how he loved me, his son and only child.

I could tell you about his failures. His two divorces, lost jobs and people tired of his endless crusading.

But at this point it’s all gone. Supported by Medicaid and Social Security, my father eats and breathes in a facility that tends to his bodily needs. A chaplain visits at least once a week, and so does a volunteer that plays CDs of music I know he used to like. His nurses and their assistants are good to him.

I visit when I feel like I can stomach the grief. Which seems less and less often these days. But who, except the nurses and nurses’ assistants would know the difference? Not my dad.

I love him so much.

But I can’t help him. When he was declining, my love made a difference. I knew.

Like when he began to have paranoid freak outs common to Alzheimer’s, I’d stand in the room with him, and hug him. I’d play Earl Hines piano jazz on my phone to distract him. It usually worked. And as painful as it was, the knowledge that I was helping him, being a good son, filled a hole for me.

I felt like I was loving him as well as I could.

But now. The shell.

There’s nothing I can do for the shell.

I miss him so much.

But he’s not gone yet.

I had already taken care of funeral arrangements. I bought a funeral package with his savings before he went into the nursing home.